Stories & Galleries

Childhood memories of the early 19th Century

Eliza (White) Root was born in 1810 and lived to be 98 years old. In 1905, three years before she died, she recorded these memories, giving us a fascinating glimpse of life in our city some 200 years ago.

“REMINISCENCES OF EARLY DAYS”

Biographical Preface in the Text

Mrs. Eliza Root, 1810 - 1905

Mrs. Root died at San Diego on February 9, 1905, at the age of ninety-five years and three months. She was a daughter of Judge Robert White, of Burlington, and a lineal descendant of Peregrine White, the first child born from the passengers of the Mayflower. At thirty-two years of age she married Elijah Root, who became chief engineer and a director of the Lake Champlain Transportation Company, building many fine steamers on that lake. He was a man known for his fidelity to duty. They had but one daughter, who married Charles Hart. Mrs. Root was a woman of strong personality, having a remarkable memory, which she retained to the last. This article is in her own language.

My grandparents on both sides located at Colchester Falls, now called Winooski. Grandfather White and family came from Middleborough, Plymouth County, Mass., in 1791. Grandfather Hawley moved in 1787.

Burlington, VT. 1846

He came with Ira Allen from Arlington, Vt., for the purpose of building mills, as he was a millwright.

He moved into the house with Ira Allen, with whom he was living when Ethan Allen died. Ethan kept a barrel of liquor in his cellar for his funeral, and he appointed my grandfather to draw the liquor at that time.

At the completion of the building of the Colchester mills, he went to Swanton and built mills there. After completing mills for Allen, he went to Shelburne and built mills for Mr. Joshua Isham, of Shelburne, who was grandfather to Rev. J. I. Bliss, of Burlington, Vt.

My mother was born in Swanton in 1787. My grandfather died in Shelburne in 1813.

In those days everything was manufactured in the family. Flax was raised from the seed, pulled, swingled, and hatcheled, the flax spun on a little wheel, the tow carded by hand and manufactured into everything necessary : summer underwear for men and women, sheets, table cloths, and towels, also summer dresses for women and children. Wool from the sheep’s back was carded, spun, woven, and made into winter garments for men and women; for women and children it was dyed blue from the tub always on the hearth, which was used for a stool, or seat-all.

I have in my possession a pocket handkerchief, copperas color, and white checked. In the fall of the year a tailor or tailoress was hired to cut and make up men’s and boys’ garments

The trimmings from paper hangings were saved for measuring, marked, and hung up for future use.

In the olden times the churches were not heated or cushioned. I remember how odd it looked after the stoves were put in the Congregational Church in Burlington, the long string of black pipes overhead. Some few ladies carried small foot stoves. One lady had a little colored boy bring and carry hers. I do not remember where he went during the service, probably sat in the “nigger pew” (*see note) with many others.

The first store of general merchandise was opened at Shelburne Point by Hubbeil & Bush. Not a store in Burlington or Colchester Falls at that time. My mother’s oldest sister told me that when she was twelve years old (in 1783, as she was born in 1771), she accompanied her father and mother on horseback from Colchester Falls to Shelburne Point for merchandise, and while there they bought her a new dress. They traveled by marked trees, forded LaPlatte River on a bar below the mouth; the store was on the north corner that leads to the shipyard, and it was afterwards burned. My uncle, L. S. White, told me that when a lad and he wanted nails, screws, or small pieces, he would dig the dirt and ashes under the store and generally found all that he wanted.

Before my remembrance, it was the fashion for elderly ladies to wear scarlet red cloaks, about three fourth length. I only saw a few, but my mother made me a coat out of one. It was trimmed with black bear’s fur on the cape, collar, and up and down the front. Prof. Lucas Hubbell, of the U. V. M., called me “ Red bird.” He frequently called, going or coming to Capt. Gid. King’s, whose step-mother, Granny King, was the professor’s aunt.

I have been told I was born November 18th, 1810. My earliest recollection is the death of my Grandmother White, January 19th, 1813, and the funeral procession moving away.

The War of 1812 left impressions on my memory. The British would come out from Canada, seize any boats that were in sight. They took a boat from Grandfather White which was owned by him and his sons. He told them it was private property, but as they walked on one end of the boat, he walked off the other.

In 1814 government appointed my father, Robert White, Harbor Master at Burlington, Vermont. The headquarters of the army were at Plattsburgh, N. Y. His duties were to take despatches or orders, sent by a row boat of six or eight men, from Plattsburgh to Burlington. He would take his boat and men and go south, with orders to scuttle the boat if they could not get out of sight of the British. Whenever they came out, the men in the lake towns would fill a wagon with feather beds and valuables that were prized, pack in the women and children, and send them to the back towns for safety. My mother with a load, women and children on top, and my uncle, L. S. White, and cousin, Capt. Dan. Lyon, started from the old place. The road for a short distance ran along the beach. One of the boys said, “Let us take our toy cannon and fire at them.” My mother,a mild spoken woman, spoke to them sharply, “Whip up your horses and out of sight as soon as you can,” causing me to look up and I saw two or three British boats with several men in them. The road ran west of Capt. George A. White’s house; the bank of the lake was skirted by cedars and other trees.

In 1814 my father was appointed Captain of Militia and Harbor Master at Burlington. I remember visiting him in his tent on the beach. He reached to a shelf, took a cake of baker’s gingerbread, broke off a piece and gave me, causing me, no doubt, to remember the time and place.

I attended school in an old building near. I thought the teacher very cruel, as he would often ferule the boys, gag them, and make them stand and hold their arms up. If they crooked their elbow the least, he would hit it with his ferule. Later I attended a select school taught by Major Murray and wife, who were English people. She was the head of the school; the Major heard the smaller classes, and Saturday forenoon he taught us the Lord’s Prayer, Golden Rule, Commandments, and Catechism, which was chosen by the parents and was mostly Westminster. The Major and his wife belonged to the Church of England. They had a daughter a little older than myself. The school room was in the west end of “Mills’ Row,” next door cast of what is now known as the Van Ness House. Hon. C. P. Van Ness lived there. One forenoon Mrs. Van Ness sent her servant girl to the school fur Miss Marcia to go home and take care of her dress, as she had been out the evening before, and her mother, going to her room, found the dress on the floor as she had stepped out of it. Mrs. Van Ness was a daughter of General Savage, who was appointed surveyor of most, or all, of the islands in the lake, taking his pay in islands.

Mrs. Murray was a careful teacher. The scholars thought it wonderful how she found out if they disobeyed their parents or told a fib. Once a month she made them stand in two lines, she at the head. They must walk down the room, turn, and say, “Good afternoon, Mrs. Murray; good afternoon,young ladies.” If she approved they would walk in the parlor; if not, we must try it over until approved. Small brothers of the young ladies were allowed to attend the school with their sisters.

Dr. Daniel Haskell, the minister of the Congregational Church, had two children who attended, Elizabeth, about my age, and Henry, younger, who ate white lead which he found in a paint shop and which caused his death. Mrs. Murray closed her school on the day of the funeral and formed her scholars in a procession, she at the head with the two smallest at each side of her. They went down to St. Paul Street, from there to Bank, where Dr. Haskell lived.

Mrs. Murray never allowed the young ladies to call each other by first name without Miss before it. When Miss Adeline White attended, I was Miss Eliza White. Oftentimes she would be out a term, and I was then Miss White, which added much to my dignity.

My uncle, Capt. Andrew White, of Cleveland, Ohio, bought land in Ionia County, Mich., and in the thirties left Cleveland to see his purchase. One day he stopped for entertainment on a lonely road, and on entering the sitting-room was greatly surprised to see a view of the U. V. M. He hurried to the kitchen to see who lived there, and met Mrs. Haskell. They were mutually pleased to meet and she told him she was making a home for her sons.

Bank Block is on the site of Howard’s Hotel of old. Near that was a moderate sized brick building with a sign reading, “Burlington Bank.” From just cast of the bank we could cross to Church Street. I remember thinking it was too bad when the Peck Block was built, making us go around the corner when we went to church.

My father was captain of a sloop for many years. About 1819 he brought from St. Johns, P. Q., a Scotch family, Mr. Fleming and wife, with several daughters and one son, Archibald Fleming, who was much respected and loved, a graduate of the U.V.M., and afterward a minister of the Gospel. He settled in Plattsburgh, N.Y., was there a year or two when his health failed him, and he came back to Burlington, and I think died in a few months. He was a brother of Mrs. Worcester, of Burlington.

Mrs. Murray saw a specimen of the Misses Fleming’s work of embroidery on cambric and engaged one of them to visit the school one afternoon in the week and teach her scholars the use of hoops and stuffing the figures; their work had been flat, or basted on paper. I worked a little cape for myself when I was nine years old. I have always used hoops since then and have used them many times since I was ninety years old.

The first cook stove I remember, my father brought home and set up in our kitchen. The oven was over the fire-box; on each side were projections called saddle-backs and in these were oval boilers. I think Mrs. Samuel Hickock had a stove about the same time.

The first piece of cotton cloth I ever saw, my father brought home; my mother showed it to the neighboring women. It was very white and smooth and was, no doubt, “India Cotton.” My father probably brought it from St. Johns. Everything was linen in those days.

All families had some provision for keeping fire in the fireplace. A bed was made in the ashes for live coals of fire which were covered with ashes; the long handled shovel was laid flat on the heap and in the morning one could rake open the fire and start it up. In case they lost the fire we had a tinder-box, a tin box the size of a brick, a cover with a hinge, and the inside divided in a square with a tin knob to raise it by. Tinder was made of linen or cotton. A piece of cotton was set on fire and when burned lay it in flat, cover to smoulder and put out the fire.

Matches were all made by hand; a section of a seasoned pine board was sawed off the length of the match, with a sharp knife and hammer, then split again the size for matches. My mother had a small iron skillet that she kept on purpose for melting brimstone. We would take five or six pieces of wood that had been prepared and dip one end in the melted brimstone, let them cool, and they were then ready for use. Also to prepare the fire, we had a flint and steel kept in a box. A piece of linen cloth set on fire until all burned over, then carefully put in the square compartment. Strike the steel and flint on the cloth cinders and then be ready with brimstone match to light your candle. I remember the surprise when our matches called “Lucifer” were first invented, it was so very wonderful.

Candles were made by hand. Rods eighteen inches long or so, candlewick cut the length of a candle, doubled to put on the rod, eight or ten on a rod, then dipped in a large boiler and put on a frame for the rods to cool on; then dipped over and over as they cooled, until large enough. We have dipped many dozen at a time.

Cotton thread always came in balls like knitting cotton. A man, a turner by trade, came to Burlington and turned spools for winding thread. I have one now which is made of bone instead of wood.

I have heard my mother say that she well remembered her first calico dress. They were living in Swanton where she was born. A man came around with blocks and colors and made calico for those who wanted it. Her mother gave him linen sheets to stamp and they then had calico dresses.

There were no postal facilities in those days. If they heard of any one going part of the distance, they would give mail matter to him to take as far as he went, and he would hear of another who would take it farther, so in about six months it would reach its destination.

When I was about eight years old I attended school at the academy, which was taught by Miss Harriet Coit. I often walked up Pearl Street, and always liked to pass the front dooryard of Mr. E. H. Deming, a merchant, as it was filled with sweet, or vernal, grass and the perfume was very fragrant to me. I wanted a root very badly, so finally mother told me I might call and ask Mr. Deming if he would give me one. I accordingly stopped at the kitchen door and asked to see Mr. Deming. The girl spoke to him, he asked me my name, and told me to go with him to the yard. He put a little clump of grass in my basket and told me how he obtained it. He said once while he was in New York, he bought a little tin pail with a few roots of sweet grass, and brought it most of the way in his hands. Traveling from New York was not an easy trip at that time,—no canals or railroads. Many merchants rode on horseback when they purchased their goods in Troy. There may have been stages, and I think there were, as I remember their blowing a horn as they were coming in.

In 1816 we lived in Burlington, and during the winter my uncle, Andrew White, went to Shelburne to visit a young lady whom he expected to marry in about a year. I went with him to visit my aunt who kept the hotel, or tavern, as it was called in those days. While there, Mingo, a runaway slave who was a servant of my father, the winter before in Swanton, called, and seeing me said, “I am going to your Grandpa’s tomorrow and I will carry you over if you like.” “How are you going?” I asked. “On foot,” was the answer, “but I will carry you on my back.” I ran into the bar-room and asked Uncle Andrew if I might go. He answered me by saying, “How would you look with your feet hanging down from a nigger’s (*see note) back?”

One day I saw a girl frying cakes, or doughnuts, over a hot fire of coals, in a kettle with lard, hung from a crane. She, with a holder in hand, was shaking the kettle all the time. I asked why she shook the kettle. “To make them rise,” she said.

I remember when “Pearlash” was used, and also when saleratus was first discovered and thought to be a great improvement. I once saw about one half pint of hardwood ashes put in a small bowl, covered with hot water, and left standing for several hours, afterwards drained off and used for, or in place of, saleratus for shortcake.

In the early days the young women wore what was then called “stays.” Grandmother White left a “stays.” The front was covered with pink “durant,” the back light brown. It was laced in the back and bound with chamois; the front was stitched and filled solid with whalebone. They were a great curiosity to me. I gave them to the University Museum, as I thought they ought to be preserved.

When I was thirteen years old my aunt thought I ought to wear corsets as I would never have a decent shape, or form, without. I cried about it and went to my father wishing him to interfere in the matter. He talked consolingly to me, but told me he did not wish to interfere in such matters. The corsets were made with a pocket in front which held a wooden busk, or board.

In 1622 the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. In 1822, the two hundredth anniversary of the event, the President of the United States appointed Thanksgiving to be observed all over the United States. My grandfather, Nathan White, invited all his and his wife’s near relatives to keep it at his house; twenty-six to thirty met and had a very pleasant time. For dinner we had turkey, chickens, loaf cake, doughnuts, nuts, and many other good things. Among the guests were Capt. G. Lathrop and Capt. Dan. Lyon. They all spent the night. We divided the beds, or made them on the floor with buffalo skins, and other things.

* Note: The "N-word"—a profane word that we loathe—appears twice in Mrs. Root's memoir. To keep this historical account intact, we have not censored the word from the text.

Additional Information

» Article about Elijah Root, husband of Eliza White Root. by Online Biographies

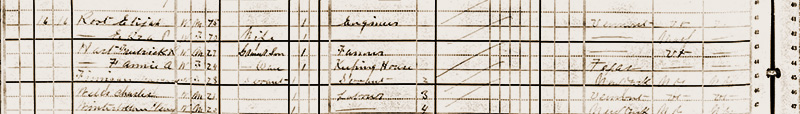

1880 United States Federal Census record of Eliza and Elijah Root. (see details by hovering mouse)

Source: The Vermont Antiquarian "A quarterly magazine devoted to the history and antiquities of Vermont and the Champlain and Connecticut valleys." Published 1904. Editors: Kate M. Cone, Byron N. Clark, Eben Putnam, T.B. Peck