Stories & Galleries

The Aftermath

What was left

after we harvested every tree in the county?

after we shipped away our wood in exchange for paper bills

which we used to build big rectangle buildings filled with

machinery, noise, and heat

which ran until they were replaced by other machines making other noises

in other places far away?

What were we to do after the fleets of wooden ships, and canal boats,

and massive steamers, were all sold away or demolished

and many of our rail cars

left to sit and rot and rust?

What were we to do with the acres of lake bottom that

were now land from our fill,

contaminated with oil and heavy metals,

corroded machines, dilapidated buildings, old tires, and all kinds

of worn-out dreams?

—Aaron Witham

Evolution of Burlington on the Waterfront

Part 5: The Aftermath

The waterfront was not always the beautiful place it is today with a beautiful bike path and board walk, nor was it always an industrial powerhouse. For most of the 20th century, the waterfront was not an ideal place according to many, but it was a place that was constantly evolving.

Trash Pile at the Waterfront (1979-1981) Photo by Tom Hudspeth, Courtesy of Special Collections in Bailey Howe Library, University of Vermont

An article from Chittenden Magazine in 1969 reads, “Somewhere, underneath all the ugly oil tanks and old buildings, behind the spreading junk car lot, there is a beautiful lakefront. But Burlington just hasn’t given it any chance to bloom, and instead has turned its greatest asset into an eyesore, darkening the face of nature in a shortsighted and insulting way… If Burlington’s lakefront is ever to offer beauty and peace to the eye and ear of her citizens, the city government must lead the way. It cannot be expected that industrial and commercial concerns will voluntarily go to the expense of moving, if the city itself refuses to have its departments do so” (17).

What happened to the waterfront after the booming lumber industry? How did people use it for most of the 20th century? When did people start to desire a different outcome, and what were their ideas? Come along for the journey!

Although there was some activity in the booming 1920s, the arrival of the Great Depression was the proverbial nail in the coffin for Burlington harbor. In 1931, an article in the Burlington Free Press reported that for the third year in a row, no freight had come to the harbor from Canada (5). By 1935, the failing lumber yards were replaced by enormous tanks for fuel storage. The tanks of the 1930s stored a whopping 5.5 million gallons (5).

Although World War II provided a boon for the local economy by employing shipbuilders at Shelburne Shipyard to support the war effort, the Burlington waterfront remained a storage location for oil. Horace Corbin, the owner of a number of ships, began selling off his ferries and steamships (5). By 1954, the last remaining steamship, the Ticonderoga, was moved to Shelburne Museum where it lives out its days sitting on land. To make matters worse, ferry fleet owner Elisha Goodsell left three yachts half sunken and derelict in the harbor (5). Meanwhile, the large cement tunnel just south of Perkins Pier in front of the water treatment facility was spewing raw sewage from the city into the harbor (5,25).

But, by the late 40s and early 50s, the city and a number of citizens began to speak up about the waterfront, and slowly an effort began to turn things around (5). But the effort would prove to be a very long process, raising a number of ethical debates about public access along the way.

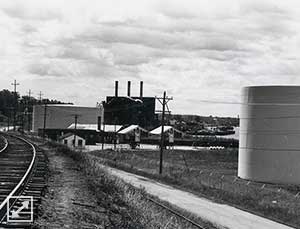

The U.S. Navy decided to locate a reserve center at the bottom of College Street near the current location of the Echo Center (5,25). Also, the Veterans of Foreign Wars decided to buy the old Timothy Follet House on College Street. And, for the first time, the city began to treat the sewage being spewed into the lake. The U.S. Coast Guard also set up a permanent base. But, other events held back the beautification process. For example, the installation of a junkyard didn’t help the area look any nicer, and the railroad companies were leaving old equipment to rust as they were being supplanted by tractor trailer trucks. Meanwhile, passenger rail service died altogether, and the Union Station became office space. But, most controversial of all was a new coal-fired power plant named the Moran Plant after the current Mayor Moran (5). The power plant, which provided the city of Burlington with its electricity, was an environmental health nuisance as it spewed soot into the neighborhoods of the old North end. Meanwhile, the oil storage along the waterfront grew. By 1958, there were 83 fuel tanks holding a total of 84 million gallons (5).

View of Moran Plant and Oil Tanks from the Urban Reserve Looking South (1979-1981), Photo by Tom Hudspeth, Courtesy of UVM Special Collections

The harbor received 280 barges of fuel annually from New York. The barges would tie up to structures like the one shown below off from Perkins Pier and hook up to the pipes. The pipes would pump oil from the barge underwater to land where they would fill up the holding tanks (25).

Other random industrial uses were scattered across the waterfront. For example a grain company named Pesco Feeds was located next to the railroad tracks (5,9). What is now Burlington Bay Café was a Texaco gas station. And, John McKenzie Bros meat-packing plant was near Perkins Pier (15).

By 1969, the waterfront was still such a marginalized place that the city of Burlington was seriously considering building an 18,000 to 25,000 KW gas turbine electric facility in the city-owned building beside the Moran plant, even though there were nine other proposed sites (17). At the time, Dr. E. Douglas McSweeney was the only alderman that opposed the construction. His sentiment was that if the city doesn’t have the will to clean up the waterfront, then who would? But, the group supporting the placement of the new turbine generator viewed increased productivity on the waterfront as a good thing as it could be an important step in cleaning up the area (17). Does this debate sound familiar? Does it remind us of the one currently taking place in the city over the re-development of the Moran plant? Do we knock it down and restore the land to a more natural beauty or do we keep the building intact and turn it into something productive? Many of the arguments about how to use the waterfront and who benefits from this use have cycled in and out of the public debate for many decades.

Different proposals in the late 60s and early 70s ranged from further beautification to giving up. For example, one group tried to install a fountain on the breakwater that would spew water into the air, but the project failed (5,25). Another proposal included the building of a nuclear facility (5). Can you imagine how the current political climate of Vermont would cope if a facility like Vermont Yankee was located in Burlington harbor?

Public opinion of the waterfront became more vocal as the oil companies storing fuel were being blamed for oil slick floating on the water and a number of accidents (5). In 1970, an article in the Chittenden magazine reads, “If it’s not worth saving [the waterfront], why don’t we use it for something else?… You see, Lake Champlain can’t clean its waters through natural purification if man continues to dump his refuse into the Champlain basin. It’s a possibility in the not too distant future, we won’t have any choice in the matter. The lake will have to be filled in for purely sanitary reasons… Do we give the lake a break now, or do we let it become condemned real estate?” (18).

Oil Storage Tanks on the Burlington Waterfront (1979-1981) Photo by Tom Hudspeth, Courtesy of Special Collections, Bailey Howe Library, University of Vermont

By 1975, the city created an ordinance that gave oil companies twenty years to vacate the property (5). Other steps in a new direction included the expansion of Lake Champlain Transportation Company’s operations at the King Street Ferry Dock, the Radison Hotel’s plan for a large hotel on Battery Street, and the Pomerleau Agency’s purchase of the historic Timothy Follet House on College Street (5). Pomerleau made extensive renovations to the house, including the refurbishing of the inside to restore it to an authentic 1800s décor, despite the fact that the improvements came with a steep price tag (25).

The Timothy Follet House (2012) Photo by Aaron Witham

In 1978, a comprehensive waterfront re-development plan was proposed by a company called Triad Ltd. out of Montreal (20). They wanted to construct numerous apartments and condominiums. The plan also included a marina, some commercial buildings, and a health club. It would take up about 10 acres of land owned by the Central Vt. Railroad. But, the city of Burlington began challenging the railroad’s ownership of the land, under the public trust doctrine. They questioned whether the railroad really owned the land beneath them that had been created by filling the water (5).

By the early 1980s, more steps were taken to clean up the area. For example, the former barge canal was declared a Superfund site by the EPA in 1981 (8). But, the big question of who really owned the filled part of the waterfront remained and developers were eager to pounce. By this time, Bernie Sanders was mayor. In November of 1982 The Burlington Free Press described the waterfront as being simultaneously an eyesore and a precious asset (16). The latest plan was being proposed by Antonio Pomerlean, a developer who wanted to put high rise condominiums along the water. This proposed development would encompass 12 acres of land which would be bought from the Grand Trunk Railroad. But, public opposition and city restrictions stood in the way. A 1982 poll conducted by a group called Citizens Waterfront showed that 81% of the 213 respondents favored public access to the waterfront. Pomerlean quickly became frustrated with the public opposition and the red tape of the city. He expressed a sentiment that seemed common to potential developers—that is, he wanted the city to decide what they wanted to do with the land once and for all and then give a developer a clear goal (20).

Mayor Sanders became an especially challenging roadblock to Pomerlean when he expressed that he didn’t want “an enclave for the wealthy” on the waterfront (20). Instead, he sided with the Citizens Waterfront Group that was demanding more public access. To this end, he wanted to transfer waterfront zoning decisions on development from the Planning Commission, which was appointed by the alderman, to the aldermen themselves because they could be held accountable by public elections.

By 1983 another plan was in the works. The Alden Corp. planned to buy land near Perkins Pier. They were cognizant of why their predecessors had failed at development, so they decided to try a different strategy. They proposed mixed use development, to avoid creating an enclave for the rich (15). But, citizen groups had already begun dreaming up their own plans (3). These included a children’s museum and playground, a natural and cultural heritage center, a native zoo, a wildlife area around the barge canal, and an amphitheater for fairs and festivals. They also envisioned an arts and craft center that would feature fine art displays, dancing, and work spaces for crafters, as well as space for a farmer’s market. In addition, they wanted to incorporate more recreational activities, such as boating, fishing, sledding, and skating. The voices for public access were growing.

In October of 1983, the Alden Corp. bought 12 acres of the waterfront from the railway. This portion was between the King Street Ferry dock and the Moran plant (13). They also bought the Green Mountain Power Company building that the city had wanted to buy (12).

The counterargument to sale of the land from the railroads to developers was that under the public trust doctrine, land artificially created by filling water can’t be owned outright by private parties. A Supreme Court case was sought to resolve the matter. If the land was found to fit the criteria of the public trust doctrine, then it would be a huge boost to the cause of public access, or it could be a bust for desirable development of the waterfront because it would be a huge barrier for any developers (22). It all depended on how you viewed the issue.

By 1986, the Moran electric plant was decommissioned (4), leaving an old building whose future is still being debated today. The land directly north of the plant known as “the North-Forty” or the “Urban Reserve” was littered with old industrial supplies, rail cars, and big oil tanks. The area was also heavily polluted (4). For a while, it appeared that the north forty’s fate would be similar to that of most other industrial uses of the area.

Abandoned Rail Road Cars (1979-1981) Photo by Tom Hudspeth, Courtesy of Special Collections, Bailey Howe Library, University of Vermont

But, momentum to finish cleaning up the waterfront was building. In 1986, the bike path along the waterfront was completed with the help of state and federal funding. Meanwhile, tourist traffic on ferry boats was increasing. Boats such as the Spirit of Ethan Allen I,II, and III all became well used boats in the harbor (5), ferries were bringing cars across the lake, and tourists were beginning to flock to the area.

The Spirit of Ethan Allen III (2012) Photo by Aaron Witham

In 1988, the new Burlington Boat House was put in place where it now floats on top of an old barge (25). The house occasionally rocks back and forth. The house was designed as part of a design contest, which was won by Marcel Beaudin, who decided to make it similar to the original.

Burlington Boathouse (2012) Photo by Aaron Witham

The dispute over ownership of the filled lands of the waterfront finally went to the Supreme Court in the late 1980s while Bernie Sanders was still mayor and Peter Clavelle was the director of CEDO (4). The city claimed the filled lands belonged to the public. In a historic ruling, the court said the filled land was “impressed by the Public Trust Doctrine”, and that industrial items that were no longer beneficial to the public such as a the storage tanks had to be removed. The city acquired 60 acres of the waterfront from the railway, and the Court directed the Vermont Legislature to make a list of acceptable uses of Public Trust Lands, which would then apply to the waterfront. The State legislature responded by defining use as “indoor or outdoor parks and recreation uses and facilities including parks and open space, marinas open to the public on a non-discriminatory basis, water dependent uses, boating and related services.” (4)

The city was now responsible for clean-up of the land and re-naturalization (4). They also placed a conservation easement on 50% of it, and restricted shoreline use within a 100 foot buffer (4). In 1991, the city was granted permission from the Legislature to develop the area between the Coast Guard station at College Street into a park. The north-forty or urban reserve was set aside for “future generations” to decide on its use, and the other areas that had previously been filled were deemed “Interim Development Areas.” (4)

In 1995, the former Naval Reserve building was taken over by the Champlain Basin Science Center (7). This center began playing an important role of building knowledge and a public appreciation about the ecology of the waterfront. Then, the building was demolished to make way for the new ECHO Center, which was supported by Senator Patrick Leahy and significant federal funds. The center’s mission epitomizes the revitalization of the waterfront as the acronym stands for “Ecology, Culture, History, and Opportunity.” (7)

By the late 1990s, it was clear the waterfront’s primary industry had become tourism and that it would be that way for the foreseeable future. But, this didn’t mean an end to the proposals for other ways to develop the area. In 1995, the railroad that owned most of the waterfront hired a planner named Colin Lindberg to develop a master plan of the waterfront. Approximately 13.2 acres would be dedicated to public use. (21). The plan included an elevator from Battery Park to the waterfront, a funicular and two large parking structures. Estimated tax revenue from the plan would be $2.8 million a year. (21).

Other ideas included the plan to build a multi-modal transit hub near the old train Station at the bottom of Main Street. The plan had some initial promise as Governor Howard Dean had re-started the passenger rail service from Charlotte to Burlington (5). The service was called “The Champlain Flyer.”

Union Station, now Main Street Landing (2012) Photo by Aaron Witham

But the transit hub plan fell apart in 2003 when public opposition arose (21). Opposition arguments included the diesel fuel ruining the pristine air of the newly cherished waterfront and the structure ruining the view from battery park. Also, public will for the plan had waned considerably after the public rail from Charlotte died in 2003 and people realized that the only other transportation connected to the facility would be seasonal from the ferries (21). In the end, many residents viewed the plan as just a glorified bus station.

Contemporary plans for the waterfront are largely focused on the area around the Moran Plant. These plans include transforming the building into an indoor ice climbing wall or demolishing the building all together. Other proposals focus on the North-40 or “Urban Reserve.” Groups like Burlington Permaculture have proposed an aquaponics facility or above-ground vegetable garden to avoid contamination from the polluted soils. Yet, other groups propose using the area to house the city’s farmer’s market. Debate about the land and how to use it will surely continue. Although the public has won the battle of public access for now, private industry can have other effects on the waterfront, especially through adjacent properties. The ongoing saga between industry and public access will likely continue as we continually re-evaluate our societal needs and desires as they relate to the interface between water and land.