Stories & Galleries

Peak of Power

You are standing between rows

of lumber 40 feet high.

The smell of sawdust

fills your nose while

the scratching of metal saws and heavy trains and

the honks of barges fills your ears.

Between the narrow rows of lumber,

you can just make out

the crystal-reflection of the water

in-between scows loaded with wood.

This is not the waterfront park

you take your dog to.

The green grass and purple lilacs and trees

are nowhere to be seen.

—Aaron Witham

Evolution of Burlington on the Waterfront

Part 2: Peak of Power

In 1817, Burlington was on the verge of the biggest boost to its economy that it would ever see. Construction was beginning on a 63-mile long canal in New York that would connect the Hudson River to Lake Champlain (5, 23). The Hudson River was the main watershed leading to New York City and to some of the biggest markets in the United States. Before the opening of the canal, the predominant direction in trade flowed from Burlington to Canada with commodities such as wool, cattle, wheat, Vermont lumber, potash, and charcoal (5).

The canal was finally completed in 1823, opening the floodgates for a complete change in the dominant flow of trade (5,23). Trade then beginning flowing south from Burlington to markets in southern New York. At the same time, steamboats were significantly increasing the volume of trade on the lake. The combination between big, powerful, and reliable ships with connectivity to New York markets created exponential growth in Burlington’s waterfront industry. Lake Champlain Steamboat Company (eventually transformed into the Champlain Transportation Company) formed in October 26th, 1826 (19). They transported passengers, as well as merchandise, goods, and wares. Their first president was William A Griswald. By 1829, they had four steamboats on the lake and by 1835, they were the owners of all the steamboats on the lake (19).

But, the big lake fairing ships like steamboats, sloops and schooners had a major limitation—they were too big to travel through the canal (5). So, they had to unload their freight onto canal boats that were then towed by horses or mules through the canal. Early entrepreneurs took advantage of this problem and designed the first sailing canal boats. Unlike normal canal boats, these boats could also sail across the lake. Moreover, they were designed to take up the maximum amount of space in the canal and carry the most cargo possible.

The new growth in the shipping industry spurred massive structural change to the harbor. In 1826, the first-federally funded lighthouse on the lake was installed on Juniper Island to replace the private lights that had been managed by citizens (5). New docks and wharves were built at Main Street, King Street, and Maple Street by 1836 (5). Many of the piers were built with stone cribwork (6). Then, in 1837, the first part of the breakwater was constructed. It would be consistently added to and maintained throughout the century (5).

But, potential warning signs of economic issues began surfacing as the Vermont forests were nearing complete liquidation (5). Ecological issues were also on the horizon, but would not gain attention until the 20th century. Because of the long narrow shape of Lake Champlain, the ratio of the basin area to the lake area is 18:1 (14). This results in a vast area for drainage into a relatively small place (14). The massive forest clear-cutting of the early 1800s resulted in a lot of sediment flowing into the basin and covering fish habitat in the lake. This is still happening to a great degree today even though many of these forests have been re-grown. From the air, huge plumes of sediment can be observed in the lake (14). This effects two key fish requirements of shelter and spawning grounds. Crevices in sunken structures, like rock formations allow fish to hide and to hide their eggs from predators. Sediment in Lake Champlain has covered many of these formations for some species (14). Now, over half the spawning habitat for some species like trout come from human-made sunken structures like old piers along Burlington’s waterfront (14).

While the Vermont forests quickly began disappearing in the late 1830’s, Canadian merchants were upset by the lack of business flowing in their direction, as most of it was being diverted to the Champlain Canal (5). In response, they started lobbying the Canadian government to build a canal that could circumvent the dangerous rapids on the Richelieu River which connected Lake Champlain to the St. Lawrence River (5).

Dominant Trade Patterns of Burlington’s Waterfront

Industry - Figure made by Aaron Witham

In 1843, the Chambly canal opened on the Richelieu River and instantly transformed the economy of the harbor once again (5). Unlike the original intent for supplies to flow north into Canada, the canal became a highway for Canadian lumber shipped south to Burlington (5). This was fueled by a tariff loophole on unfinished lumber imported from Canada (1, 23). Finished lumber had a tariff, but not undressed lumber. Therefore, local lumber barons could import it for free, finish it in Burlington, and then sell it to markets in the United States for cheaper than the going rate of lumber that was cut in the U.S. (1,23).

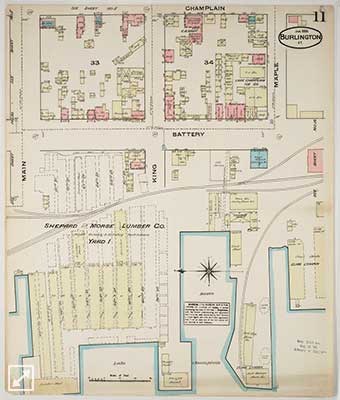

By 1875, the J.R. Booth Lumber Company had arrived, and they were the largest owner of timber lands in Canada (19). Now, logs and timber from Canada piled high along the waterfront, where it was then re-shipped to other markets throughout New England (5). Tug boats led square-rigged boats known as “pinflats” stacked high with lumber into Burlington harbor from Canada via the Chambly canal on the Richelieu River which connected to the St. Lawrence (1). A single tow-line could bring up to 50 pin-flats. The individual canal boats were brought to specific locations along the harbor by local day laborers known as “lumpers.” (1). Most of the property adjacent to the water was divided into tiny streets or paths where lumber could be stacked on either side. The names of these streets on early fire insurance maps were numbers, like 24th street, for example (27).

Just when it seemed the waterfront couldn’t get any busier, the railroads came to Burlington in 1849 (5,23). The effect of the railroads were enormous because year-round stable transportation was now possible. Before the railroads, only limited transportation occurred on the lake via horse-drawn sleighs. Thus began the most active industrial stage of the Burlington waterfront’s entire history. Lumber would serve as the backbone of the economy for the rest of the century.

Portion of a Sandborn Fire Map (1811). Notice the lumber yards by the water. Courtesy of Special Collections in Bailey Howe Library, University of Vermont

The arrival of the railroads spurred a second major alteration of the waterfront’s structural appearance. Curtis Holgate built “south wharf” at the bottom of Maple Street and filled some of the lake to accommodate it (23). Then, the Rutland and Burlington Railroad Company also filled some land to make way for more tracks (23). A coal merchant named George Beckwith built a 100-foot long pier south of Maple Street. Additional water was also filled south of this pier where the water treatment plant currently stands. Some of the fill was created by placing old ship hulls filled with rocks or gravel into the water (23). It is likely that a lot of material for fill came from local sources, including the steep bank at the water’s edge. (6). So, it’s possible that the bank extended out quite a bit further than it currently does (6).

In 1850, the booming industrial waterfront stumbled a bit from the closing of the prominent Champlain Glassworks factory (5,23). This was concerning for the dozens of wealthy businessmen who had been making a fortune off Burlington’s shipping industry and newly created connectivity to inland New York and Canada. Burlington was shipping lumber but it wasn’t producing as many commodities as it used to. Rather, it was purchasing these commodities from far away. In 1852, a group of local businessmen took it upon themselves to find a way to make local items again (23). The effort seems familiar to the current cultural trend in Vermont to buy local whenever possible (25).

A Fire near the Harbor (1888). This is not the same fire that burned the Pioneer Shops. Courtesy of Special Collections in the Bailey Howe Library, University of Vermont

But, after the fire, the building was replaced by three new buildings, some of which still survive today (5). The factories produced iron castings, furniture and other items (5). The world famous Venetian Blind Company was started there (25). They made the original blinds for the Empire State Building (25).

Manufacturing became a strong element of the economy by the 1870s, and many of these items were shipped all around New England and to New York City and Canada. Some of the notable manufacturers were Burlington Cotton Mills on Pine and St. Paul Streets, J.W. Goodell’s granite and marble items, Arbuckle and Co’s candy, S. Beach’s crackers, Reed and Taylor’s cigars, Matthews and Hickok’s boxes, and Burlington Manufacturing Co’s nails (2).

One of the Pioneer Shop Buildings (2012)

Photo by Aaron Witham

Another Pioneer Shop Building (2012)

Photo by Aaron Witham

Meanwhile, the lumber industry resumed its boom, hiring a large immigrant labor force from Canada and Ireland (23). Large ships on the lake and the railroads complemented each other with heavy shipments coming by water being timed to match rail schedules for shipment to other places. By 1860, Burlington had become the most populated city in the state (23). In 1865, the city had become the third, maybe even second most important and largest lumber port in the United States, behind only Chicago and Albany (5, 29). In 1866, The Burlington Free Press reported that 60 million feet of lumber were delivered to the harbor along with one million bushels of grain, and a total of 2,563 shipping vessels had unloaded cargo (5). In 1868, the lumber had grown to 112 million feet, representing $3 million in business. 475 canal boats arrived that year and 3,778 railroad cars were shipped (5). But, by 1873 Burlington was handling upwards of 123 million feet of lumber a year (5). And, at its peak in 1889, shipments topped 375 million feet (23).

Because the lake froze over in the winter, the lumber yards would have to stock up on lumber. So, they worked hard in the summer months to create a large inventory (1). Large Canadian barges called “Pin Plats” filled with lumber arrived every day in the harbor (5). The lumber was stacked 30-40 feet high and covered over 30 acres of waterfront area (5). Storage space became a huge issue, and therefore, every available spot along the water was taken (1). The situation got so dire that in 1866, lumber Baron Lawrence Barres, the largest in town, had to stack lumber on the breakwater! (1). The space constraint inspired Lawrence Barnes to build the barge canal in a large wetland area south of Perkins Pier (Click here to read more about the Pine Street Barge Canal). By this time, there were at least 12 wharves in the harbor (5).

Lumber Yard from Battery Park (1860-1880) Courtesy of Special Collections in the Bailey Howe Library, University of Vermont

Within a few years, coal became another major commodity in addition to lumber because the trains had converted their engines from wood to coal (1). Fleets of scows loaded with coal were towed by steamers and tugs into the harbor from Albany and Hoboken, NY. The companies shipping it included the Lake Champlain Transportation Company and to a lesser extent, the Northern Boatman’s Association (1). By 1874, a large coal shed was built to accommodate the Rutland Railroad’s need for more coal after converting their engines from wood to coal (1). By 1884, the coal shipped to Burlington harbor was not only used for the railroads, but it was sold to citizens and re-shipped to other places, creating a wholesale market. Coal dealers from as far away as New Hampshire and Canada began receiving coal from Burlington. Workers known as “heavers” were paid 20 cents an hour to remove bucketfuls of coal from the scows. 75,000 gross tons came through the waterfront annually (1). Most of it was for household use, but about 3,000 tons were dealt to commercial buyers. Coal dealers included Elias Lyman, George C. Linsley, Adsit, and Bigelow (1).

Another lesser known industry was the commercial fishing industry that existed throughout the 1800’s. It included white fish, trout, and salmon which were sold to markets in Boston (14). But, by the early 1900’s, this industry was largely replaced by tourism and helping tourists catch their own fish.

A final, very important industry was started during this time: tourism (5). After the Civil War, steamboat and railroad companies began marketing the Burlington waterfront to vacationers. The first large hotel resorts and campsites were created at this time (5). Even small recreational boats started to appear along the waterfront—a premonition of the next century. In the late 1880s, the Lake Champlain Ice Boating Club and the Lake Champlain Yacht Club were both formed.

By this time, the waterfront was on the verge of a massive sea-change. In 1872, the Lake George Steamboat Company formed, and by 1880, competition between them and the Lake Champlain Transportation Company was stiff as both companies also had to compete with the railroads (5). Steamboats were forced to slash their fares. Sailing canal boats were also on a fast decline. Using canal boats was only economical for heavy commodities like coal, iron ore, lumber, or stone. The fact that it was rarely cost effective to ship through the lake began eroding the utility of the lake itself and led to the decline of industry at the lakefront (5). By 1876, it was clear that the shipping industry on the water would never be what it once was. A decline in the utility of the water was a major blow to the vibrant industrial activity of the waterfront. But, the second blow would break the waterfront’s back.

New tariffs on unfinished lumber in 1893 and 1894 drastically reduced the volume of imported lumber from Canada (5). Canada begin shipping to other markets in other cities. Most lumber mills began to close in the mid 1880s, and were replaced by the first oil storage units, symbolizing the end of one era and the beginning of another. Standard Oil of Burlington constructed four large tanks (5).

The rise of the automobile was imminent. It would kill the wooden ships and the steamboats, and drastically reduce the volume of rail. By 1926, the lumber industry was all but dead as the harbor only received 30 boats of lumber a year (5).The trucking industry made the waterfront a shell of its former self, but new diesel powered barges and ferries arrived in the harbor trying to entice cars to cross the lake to save driving time (5). But, the construction of the Champlain Bridge in 1929 made the ferry service much less appealing (5). It wasn’t long before the waterfront became a massive storage facility to fuel this new dominance of automobiles (25). Most waterfront shipments were now oil barges coming from the Champlain canal.

The connectivity that once opened the gates for booming industry would begin opening the gates for aquatic invasive species from other places, such as the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers. One example of an invasive transported through this connectivity was zebra mussels (14). The shell of 19th century industry would also leave other marks, like a polluted barge canal, heavy metals in the soil, and dozens of acres of filled land now holding giant oil tanks or derelict industrial equipment.