Stories & Galleries

Make Way, Froggies

Our dreams are big,

big enough for 150 men

and a fleet of horse carts and wheelbarrows

to dredge a frog swamp into a canal

for barges loaded with 100,000 feet of lumber,

or a line of scows carrying 600 tons of coal.

But, our memories, even our lives,

are shorter than this.

short enough to sometimes forget that the little inlet

between Perkins Pier and Oak Ledge

is not a river,

but a barge canal,

a human-made show of might,

framed by two wharfs

that have sunken beneath the water,

as the lake and the land

begin to reclaim

what was theirs.

Indeed the cattails have sprung from the banks,

and the frogs have returned to their home,

though they too have forgotten

what it once was.

—Aaron Witham

Evolution of Burlington on the Waterfront

Part 3: “Make Way, Froggies”

By the 1860s, Burlington harbor was importing massive amounts of lumber from Canada. Lawrence Barnes was one of the largest of the lumber dealers in town and he owned a lot of land (1). But, he didn’t own enough land for storing the amount of lumber that needed to be stored. Because the lake froze over in the winter impeding shipments via water from Canada, lumber companies had to stockpile massive inventories to keep business flowing through the colder months. But, space was running out along the water, and they could only stack the lumber so high. It got so tight, that in 1866, Lawrence Barnes was forced to stack lumber on the breakwater! Seeing no other reasonable options, Barnes thought he might be able to make use of the wetland that he owned south of Perkins Pier. He needed more space to stack lumber and more waterfront area to unload the lumber. So, he decided to create the barge canal (1).

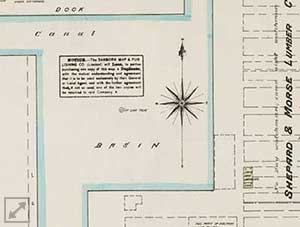

Construction broke ground in August of 1868 (1). One-hundred and fifty men armed with wheelbarrows and horse carts were tasked with the project. They first dug a basin area that was 2 acres and 20 feet deep. The entrance was 100 feet long, and 20 feet deep. The railroad tracks ran over it on top of a drawbridge. This wooden structure was not a normal drawbridge because it opened like a jackknife until 1919 when it was finally replaced by a real drawbridge made of iron.

The men also dug canals on both sides of the basin. The Southern one was 500 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 12 feet deep. The northern one was 600 feet long, 50 feet wide, and 12 feet deep (1). The material dredged from the canal was used to build up the sides to support stacks of lumber. The men also built piers to serve as breakwaters to protect the entrance. The north pier was smaller, about 100 feet long. The southern one extended 700 feet.

The side of the canal adjacent to the waterfront was owned by Rutland Rail Road Company in 1869 (27). Within the barge canal, the land to the east was divided into short paths where lumber could be stacked. It was owned by Shepard, Davis and Company to the south, and Kilburn and Gates to the North. Like the other parts of the waterfront, the paths in the lumber yards were labeled with numbers rather than names. They ran perpendicular to the lake front. The northwestern portion of the inside was owned by S.K. Wells and it served as a coal yard and coal shed (27). The shed extended 300 feet long and 60 feet wide. Other adjacent landowners around this time included Flint and Hall who owned seven acres on the east side, and A.G. Stearns who owned land on the north side (1).

After the canal was finished, a local newspaper described the scene in 1869 (1). Their description seems less concerned about the frogs, and more delighted with the economic progress. But, what do you think?

“Since the first of September 106 barges loaded with lumber have been received at the Cove lumber yard of Messrs. Shephard, Davis, and Co. including those now unloading. Each barge having an average of over 100,000 feet, this gives according to the estimates of the wharf-master, something in the neighborhood of 12 million feet received, unloaded and piled, within the last seventy days, or about 170,000 feet per day. When we take consideration the fact that the site of this yard was a number one frog pond a year ago, it has the appearance of being quite an energetic ‘change of base.’” (1).

Within a few years, coal became a major part of the barge canal as fleets of scows loaded with coal were towed by steamers and tugs into the harbor from Albany and Hoboken, NY. The companies shipping it included the Lake Champlain Transportation Company and to a lesser extent, the Northern Boatman’s Association (1). By 1874, a large coal shed was built to accommodate the Rutland Railroad’s need for more coal after converting their engines from wood to coal (1).

By 1884, the coal shipped to Burlington harbor was not only used for the railroads, but it was sold to citizens and re-shipped to other places, creating a wholesale market. Coal dealers from as far away as New Hampshire or Canada began receiving coal from Burlington. Workers

known as “heavers” were paid 20 cents an hour to remove bucketfuls of coal from the scows. 75,000 gross tons came through the waterfront annually (1). Most of it was for household use, but about 3,000 tons were dealt to commercial buyers.Use of the barge canal declined significantly near the turn of the century as the lumber and coal trade was replaced by petroleum storage (5). The land previously dedicated to stacking lumber was supplanted by large oil tanks. Barges bringing oil didn’t have to dock on shore. They could pull up to stations offshore and pump their oil through underwater pipes (25).

By 1981, the EPA designated the old barge canal a Superfund Site because of the significant pollution there (8). For more about the ecological importance of the sunken wharfs near the barge canal, click here!